Glenkerry Lockdown Exhibition

Welcome to the Glenkerry Online Art Exhibition. This project brings together a collection of works submitted by our residents during 2020, in response to the lockdowns due to the COVID-19 virus.

The original idea was to invite residents to send something of their choice that they'd been working on, representing snapshots of life in our building during a time when everyone was isolated. It was intended that the project would bring a sense of togetherness and inclusivity, at a time when people could only interact with neighbours virtually or at a distance. The project has prompted a huge response in terms of participation, showcasing a wealth of talent from behind the doors of our block.

There are four rooms in our virtual gallery. Room 1 features paintings and drawings. Room 2 contains images that come with a story. Room 3 has written pieces inspired by Glenkerry or the lockdown. Room 4 contains audio and video pieces featuring Glenkerry House. We proudly launch the collection, and hope that you really enjoy it!

Room 1: Paintings and drawings

In this room we present a variety of paintings and drawings, from vibrant watercolours and atmospheric photographs to striking abstracts, inspired by Glenkerry House and the surrounding areas.

CORRIDOR 3 Acrylic on newspaper: Vicky Dale

WINDOW 2 Acrylic on newspaper: Vicky Dale

BIG BRISTLY PIG, MUDCHUTE Charcoal (digital copy): Katie John

BOBBY, MUDCHUTE Pencil: Katie John

PIG STUDIES, MUDCHUTE Charcoal pencil: Katie John

NOISY SHEEP, MUDCHUTE Charcoal: Katie John

AUTUMN, BROWNFIELD ESTATE Photograph: Sonja Mills

GLENKERRY SUNSET Photograph: Sonja Mills

RAIN OVER POPLAR Photograph: Sonja Mills

MYSTERIOUS VAN, ROBIN HOOD LANE Photograph: Waen Shepherd

WARM SHAVINGS Collage: Waen Shepherd

MANDELBROT OVERLAY Digital artwork: Rex Smith

TRILOBITE 2020 Digital artwork: Rex Smith

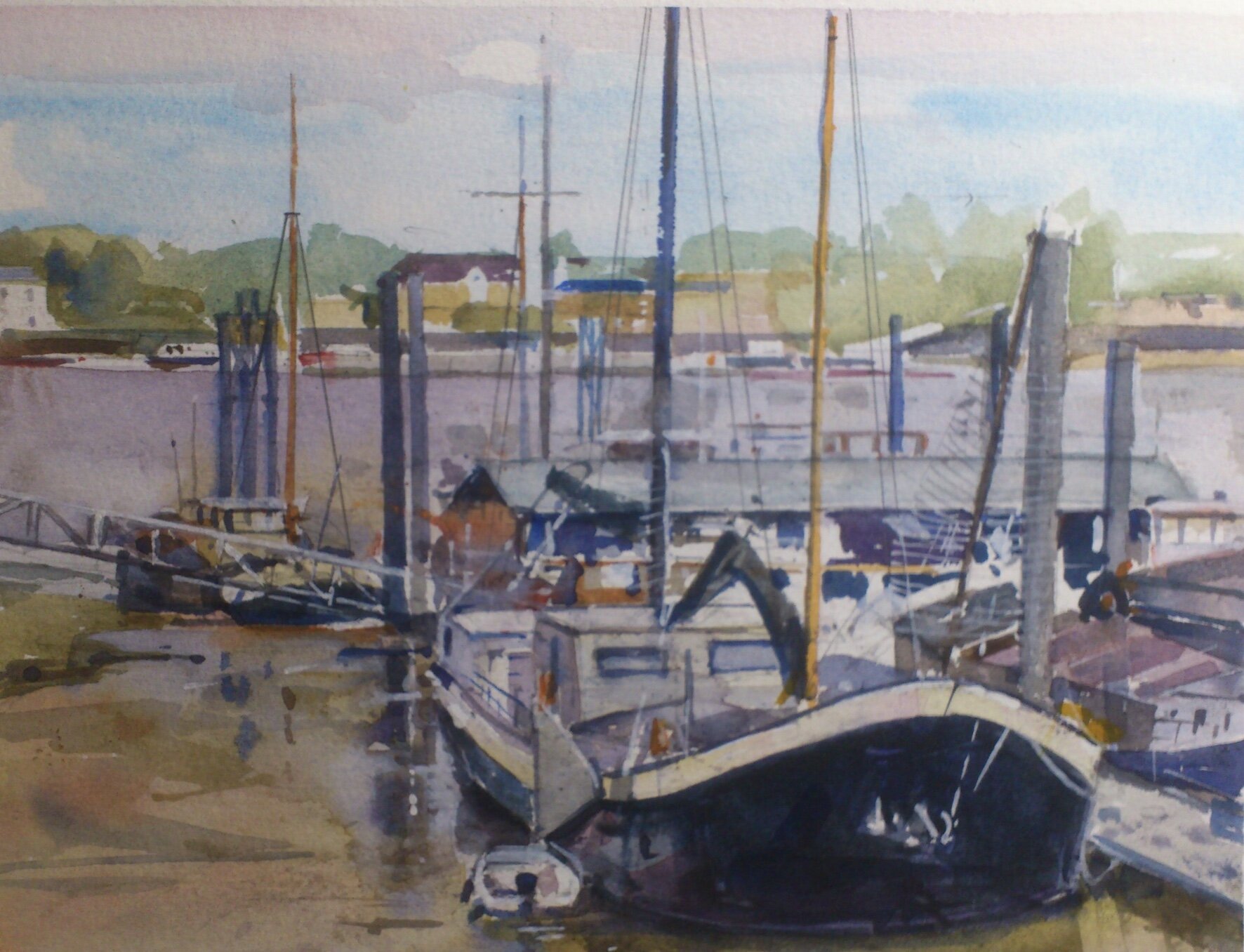

BARGE Watercolour: Eric Underwood

BOATS AT TOWER BRIDGE Watercolour: Eric Underwood

BRIGHT STREET Watercolour: Eric Underwood

THE DOME FROM THE RIVER LEA Watercolour: Eric Underwood

ISLAND GARDENS Watercolour: Eric Underwood

LIMEHOUSE CUT Watercolour: Eric Underwood

THREE MILLS Watercolour: Eric Underwood

TOWER BRIDGE Watercolour Eric Underwood

Room 2: Images and stories

In this gallery, we show an eclectic group of pieces in unusual media. Here, each artist has given a brief description of what inspired them to make the piece.

Nautical knots

Repurposed objects

Marie Chillmaid

A little upcycling/repurposing, which I love doing. I bought an old picture in a charity shop for £3, showing boating knots, took it apart, remounted the pieces on new backing card, and framed them as a set of 3.

Breakfast Man With Boobs

Food collage

Katy Darby

A record of a holy miracle which happened towards the end of lockdown, when an egg was found with two yolks and the food formed itself onto the plate in the shape of a two-boobed man.

Ties

Textiles

Geraldine Parkes

I was asked to make this by a friend, who wanted a reminder of his old ties. I found a suitable patchwork pattern, although it was a bit difficult working with the different fabrics. They were different weights, so it was tricky to get things reasonably accurate. Anyway, the main thing was that he was pleased with the result.

The Ghoul (album cover)

Digital artwork

Waen Shepherd

This work was made for the album cover of the original soundtrack that I composed for the film The Ghoul. The album was released on Friday 26 June. Further details can be found here:

Recursive Self-portrait

Photography and mixed media

Waen Shepherd

For the Online Gallery Project – a sequence of four self-portraits from 2006 to 2020, designed to illustrate the catastrophic effect of lockdown on the number of people in the average person’s social circle.

Room 3: Writing

This small gallery features three stories and a poem inspired by life in Glenkerry.

For the Good Times

A story in 100 words by Katie John

I was touched that the family asked me to Ron’s funeral. I’d just done what neighbours do – look in on him every now and then, after Doreen died, once he started getting frail and ill.

The service ended with the song Ron and Doreen danced to at their wedding, all those years ago – Perry Como, “For the Good Times”. That warm, familiar voice drifted over us … and suddenly I saw them at the front there, holding each other and swaying together one last time.

My eyes blurred. Then a shaft of sunlight shone through the window, and they were gone.

A Virus Verse

by Rob Munday

The days drift one into another

in watercolour time

a daily blur to greet you

and tell you that you're fine

Interior microclimates

develop in your wake

a mix of farts and sunshine

a trail of dust and cake

crumbs.

I'll clear that up at some point

I'll reply to that text message

I'll make those plans and do those things

(like think of something that rhymes with message).

Until then I'll sit

perhaps something will happen.

EDNA’S GIFT

Katie John

I wrote this story in 2014 as part of a writing workshop held on the Brownfield Estate and run by artist Lucy Harrison. The exercise involved walking around the neighbourhood and creating a story based on one of the people we saw on the walk.

Edna was having a lovely morning. As she chatted to her friend Betty and sipped a leisurely cup of coffee, she enjoyed the sunshine and warmth. She always kept herself nice, but today she’d decided to wear her print top and black trousers, make a special effort. Betty was wearing her glamorous sunglasses. “We look like a pair of film stars!” Betty giggled.

Just then Edna’s mobile bleeped. “Hang on a second, Bet – message for me,” said Edna, cutting off Betty’s flow. She took a drag on her cigarette and found the text message. It was from her grand-daughter Courtney.

“I’ve got the place Nan”, it said.

Edna beamed.

“What is it?” said Betty.

“Our Courtney’s got that job!” said Edna.

“What – the mechanic’s one?”

“No – engineering apprentice! She’s going to start with Rolls-Royce!”

“Doing what?” said Betty, squinting at her friend.

“Building engines for planes.”

“Fancy that!” said Betty. Her tone suggested that she was trying to be encouraging, but the doubt showed on her face. She sighed.

“I’m all for equality – but isn’t that a funny kind of a job for a girl?”

Edna’s eyes narrowed. She took a sip of coffee so she wouldn’t say anything by accident. From far back in her memory, she heard another, harder voice: “That’s no job for a woman!”

Her old ma. God rest her soul.

————-

It was 1954. Edna had just started her first full-time job, in a grocer’s on Poplar High Street. This particular evening, September time, she had stayed late to help the grocer tidy up.

Edna was walking back up Ida Street with a bag of veg for her ma. She turned the corner into Burcham Street.

“Stop right there, miss!” A soldier blocked her way.

“We been invaded, then?” said Edna, pertly.

“No, miss. I must ask you to stay back. We’ve found some unexploded ordnance. We will be clearing the area.”

Behind the soldier, Edna could see another man, crouching and peering into a hole in the ground. Edna knew the council were clearing this area for building work. They must have found something left over from the war.

“Ooh – a bomb!” said Edna, widening her eyes at the soldier.

“I must ask you to leave,” said the soldier.

“But my house is just down there!” Edna protested, pointing down the street. “Can’t I just run past really quickly before you blow us all up?”

The soldier scowled. Just then the other man came up and whispered in his ear.

“What do you mean, you can’t get to the wires?” the soldier said to his mate.

“We can see what’s in there, Sarge,” said the other man, “but we can’t reach it. Gap’s too small. Buggering Jerrys – pardon my French, miss.”

Edna stifled a laugh.

The sergeant was quiet for a few moments. He rubbed a hand across his face. “We can’t get extra help out from the base – it’ll take them an hour to get here.”

He glanced at Edna, and stepped back. Taking his colleague by the arm, he said in a low voice, “If we can’t defuse it now, we will have to evacuate the area and get a full team in in the morning. Are you sure there’s no other way?”

“If I could find one, I would,” said the other soldier. “But that housing is so small, you’d need a midget’s hand to reach in there.”

Edna didn’t know what made her say it, but she suddenly spoke up. “I could help if you like! I can do wiring!”

The two men stared at her, hard. There was a small silence.

“I’ve done stuff before!” Edna continued, before she could stop herself. “I’m always wiring things for my ma!”

That was true. Ever since her father, a merchant seaman, had left them to start a new life in South America, Edna had had to learn all sorts of DIY jobs to help her ma.

The soldiers looked at each other.

“No,” said the sergeant flatly. “Absolutely not. Thank you, miss, but it’s much too dangerous.”

“But how will you clear everyone out in time?” said Edna. “Some of the folks here are old – they’d take forever to get going. Where would we go to be safe? Squashed in the church again, like in the war?”

The sergeant frowned and looked at his boots. He beckoned to his colleague and they walked away a few steps. They had a short, whispered discussion.

The sergeant came back. His face was set.

“All right, miss,” he said. “Come this way. Watch where you’re walking.”

The three of them approached the hole. Edna caught sight of the bomb. Its curved metal casing gleamed dully. She shivered.

“Just listen to Simons here,” the sergeant said quietly. “Do exactly as he says.”

Simons pointed to the end of the bomb casing, where a panel had been removed. Edna could see a mechanism with wires leading from it.

“We need you to reach in and gently detach these wires from the terminals,” said Simons. “Be very careful not to let the wires touch each other.”

For fifteen very long, very quiet minutes, Edna felt inside the metal structure and gently, strand by strand, teased the wires away from their attachments.

“That’s one,” she said, after a few minutes, letting herself breathe again. She twisted slightly to reach the two remaining wires.

“Careful, miss.”

“I know!”

Edna held her breath as much as she could. She squinted, although she couldn’t see anything. The sergeant and Simons watched anxiously, but she tried not to look at them.

Then, finally, “Done it!” she said.

Simons darted forwards and peered into the bomb. He shone a torch inside it. Then he sat back on his heels and looked up at Edna.

“Lovely job, miss!” he said. “You’ve got a real gift there. You can come home and do my plugs if you like!”

“Now then, Simons …” said the sergeant.

The sergeant went to their car and returned with a piece of paper. He offered it to Edna, with a fountain pen.

“I have to ask you to sign this, miss,” he said.

Edna read the form. It was for people who assisted the armed forces in certain tasks. The sergeant had already ticked a box saying “Sensitive/secret work”.

“You mustn’t tell anyone about what happened here this evening,” said the sergeant. “This form makes it legal – like the Official Secrets Act.”

Edna signed the form and gave it back. The two men shook her hand.

“We are enormously grateful,” said the sergeant. “Safe home, now.”

—————

“What are you grinning for?” said Edna’s ma, when Edna got in.

Edna put the veg on the table. She was bursting to say, but she couldn’t.

“I want to get a job!” she blurted.

“You’ve got one,” said her ma.

“No – a real one – I want to be an electrician!”

“The very idea,” said Ma. Her tone warned Edna not to take this any further.

Edna carried on. “But I can do loads of electrical stuff!” The bomb, with its network of wiring, flashed into her mind. “I know what to do – I do it for you already! I’m as good as any man!”

Ma’s face darkened. Her lips grew dangerously thin.

“Now, you look here, madam. If you go getting ideas like that, what man’s going to want you? He’ll think you’re nearly a man yourself. No – you stick to what you’ve got. You’ll have a nice little job and find a nice fella, and get married and have kids like a normal person. Know your place.”

Edna’s eyes burned, but she knew better than to argue when Ma was in this sort of mood. She turned and ran out of the kitchen.

“Electrician!” Ma called after her. “That’s no job for a woman!”

So Edna behaved herself and got a little job and a nice fella, like a normal person. She had tried a couple more times to talk to her ma about being an electrician, but each time she got the Look of Death, so she finally dropped the subject.

Still, she hadn’t done too badly, though. She and Bob had lasted for 45 years, until the cancer got him. Her children had done well. John had emigrated to Australia, where he ran his own construction firm. David was in the Army. Pauline had a good job with the council.

Pauline’s youngest, Courtney, was the brains of the family.

Edna read the text again. She smiled at Betty.

“I wouldn’t stop her for the world. She’s got a real gift for it, you know.”

RETURN TO BROWNFIELD

Katie John

This is another story that I wrote in 2014 during Lucy Harrison’s writing workshop on the Brownfield Estate. In this exercise, Lucy asked us to write a story based on our ideas about what the estate might be like in the future – say 20 years from now.

The estate looked much bigger than I had remembered as I jumped off my horse and approached the iron gate. I wasn’t sure that they would let me in, but I was so desperate it was worth a try.

I banged on the gate, startling my horse. A shutter slammed back from a small metal grille at eye level.

“Yes? What d’you want?” said a man’s voice. A pale blue eye met my gaze.

“Sanctuary,” I told him.

“We don’t allow strangers in here.”

I took a breath. “I used to live here,” I said. “I was one of the First Ones.”

“Prove it,” said the man.

“OK,” I said. “The name of the First Garden – it was called Greening Brownfield.”

There was a short pause.

“Hold on,” said the man.

I stood back as he opened the gate for me and my horse. He slammed it shut behind us.

I knew why he was so cautious. He thought I was from the countryside. Easy assumption to make, as I had come down the A12 greenway. I guessed they had lookouts at the top of Balfron Tower.

In the 20 years since I had left Glenkerry House, to move to East Anglia, the whole country had suffered a convulsion. The people in the big cities – London, Manchester, Leeds, Swansea, Glasgow – had been the first to see the trouble coming. Peak oil meant that urban life would have to change radically if it was to survive. Car travel became a rarity – you had to have good money, and a good reason, to hire an e-car. Similarly, air travel had dwindled to become a luxury again.

In the cities, waste ground, motorway central reservations, and roundabouts became allotments – food no longer came from abroad, and even produce from out of town was hard to come by. Whatever spaces could not grow vegetables were left to run wild for donkeys, goats, chickens and even bees. Every roof had solar panels. Every house had composting toilets.

Meanwhile, the countryside had become the fiefdom of the rich. Huge swathes of East Anglia had been turned over to genetically engineered crops; these, and water, were the new currency of wealth. The uplands and moors were now playgrounds for country sports. Ordinary people could no longer afford to live in villages. The intensive agriculture and extravagant use of water was killing the wildlife; in some rural areas you could go for days without hearing a bird sing.

People left the countryside as they could no longer cope there, and headed to the cities – like the Industrial Revolution all over again. Once my Mum died, I knew I would have to do the same.

The man showed me a patch on Jolly’s Green where I could leave my horse to graze.

“Thanks for letting me in,” I said. “I’m Katie, by the way.”

“Erik,” said the man, shaking my hand. He pointed at the top of Balfron Tower. “Our lookouts spotted you and tracked you by camera.”

“What do you use?” I asked him, “Drones?”

Erik laughed. He took a thick glove from his belt and put it on, then gave a piercing whistle and waved to the sky.

A black dot tipped off the rain spout at the top of the tower and plummeted towards us. I ducked as the peregrine falcon swooped and settled on Erik’s fist. I noticed that the bird was fitted with a tiny camera.

“Good girl, Isis!” Erik said, stroking the falcon. He pointed at the camera. “Karim upstairs made it. He hacked into the existing CCTV system to link these up to it. All the falcons wear them. They do a great job patrolling our borders for us. They also bring us the odd rat or pigeon to eat if we ask them nicely.”

He turned and beckoned me to follow him. “Fancy coming up for a brew?”

I was parched after my journey. I nodded.

I glanced at the lifts as we entered Glenkerry House, but Erik headed straight for the stairs. He saw my wistful look. “Luxury,” he said, shaking his head. “We don’t have power to run them.”

We climbed set after set of stairs, pausing as I struggled to overcome my terrible stitch. Finally, we reached a landing, then a corridor, then a red door with a shining sun painted on it.

Erik had to knock a couple of times before the door opened. A dark, smiling, bearded face met him.

“Karim, my man!” Erik said. “We have a guest!”

Karim smiled at me and gestured for me to come in.

His flat was like the inside of a giant beast. Pipes and wiring ran everywhere. Several old computers sat brooding in nests of cable. In one room were trays of plants, drip-fed through thin pipes; solar blinds were unfurled at two of the windows.

Karim went to make the tea.

“Where do you get the water from?” I asked Erik.

“We collect rainwater from the roof. Store it in tanks in the kitchen, and in the old toilet cisterns. We recycle our own piss.”

I glanced towards the kitchen with sudden concern. Erik grinned wickedly.

“Everything filtered five times, of course.”

I turned towards the room with the plants. “Hydroponics?”

Erik led the way inside. “That’s just the start of it. We’re breeding them and testing their DNA to make them more nutritious. It’s not genetic engineering like the rich sods are doing – this is a natural system, led by the plants themselves. We call it “enhanced DNA” – or “eDNA”.

I raised my eyebrows and smiled, then I went to the window and looked down. From this height my horse was a small brown blob. I looked further, to the greenway stretching towards Stratford, and to the lights coming on across the city. It looked quiet, green, and safe after the ravaged countryside.

I smiled back at Erik. “I like what you’ve done to the place,” I said.

Room 4: Sound and vision

We end the exhibition with a selection of audio/video pieces. The first two are taken from life in Glenkerry - one featuring the natural world around us, and one capturing the noises of the building itself. The last one is a video with music by Glenkerry resident John Pulman, together with a link to the Twitter thread connected to the piece.

GK Sound Drawing

Mixed media

Esther Ainsworth

This image is from a series of drawings that go with my “GK Skylines” sound recordings: gestures responding to the sounds on our estate. The recordings were all made during lockdown, at dawn when the world belonged to nature. This is a 5-minute soundscape, composed of a series of recordings from my balcony.

Click on the arrow to the right to listen to the soundscape while viewing the image.

Glenkerry Sounds

John Pulman

A combination of video and animation, made as part of the residents' creative art and online gallery project: a response to lockdown within Glenkerry House

Go to the Child

Go to the Child is a poem by Imtiaz Dharker, a Queen’s Gold Medal-winning poet, written for the BBC Radio 3 Breakfast Carol Competition 2019. The competition invited amateur composers to create new music for the poem. Imtiaz kindly gave me permission to use her poem to create the above version, sung by Karen Harris, John Pulman and Santos Luzon. It was not entered into the competition, but is presented here with my short essay on refugees (hand-written by Karen). It is illustrated with photos by Giles Duley, a documentary photographer and writer, who kindly gave me permission to use his pictures. He is best known for his work documenting the long-term impact of war and is CEO of the Legacy of War Foundation and activist for the rights of those living with disabilities caused by conflict.

There is further information on the issues connected with this film in the following Twitter thread: https://twitter.com/jplumbum/status/1334897315799310339